But autobiographical comics about illness, known as “graphic medicine”, provide a different picture.

These comics capture what it’s like to be sick, undergo treatment or take on caring responsibilities. They visualise physical, cognitive and emotional symptoms that are difficult to communicate. They inject a human element into medicalised spaces, pushing back against data-driven, objective notions of the human condition.

These comics are found in print, online and on social media. One of the most famous examples is Allie Brosh’s Hyperbole and a Half. Beginning as a daily blog in 2009, it has since become a phenomenon.

Brosh’s early posts – featuring hilarious anecdotes of early childhood misadventures – quickly attracted a dedicated readership. But in 2013, the two-part series revealing her ongoing struggle with severe depression went viral: Depression Part Two received over 1.5 million views in a single day.

The phrase “graphic medicine” was coined by comics artist and physician Ian Williams in 2007. Broadly referring to the intersection of comics and healthcare, the beginnings of the movement date back almost 50 years.

Across America between 1963 and 1975, artists and publishers of the Underground Comix movement produced small-press comics challenging contemporary taboos.

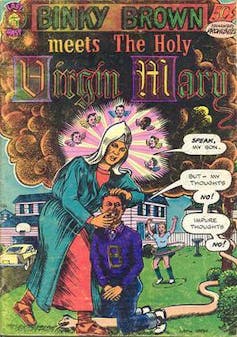

The first autobiographical comic from the underground, Justin Green’s Binky Brown Meets the Holy Virgin Mary (1972), was also a formative work of graphic medicine.

Following a young man living with undiagnosed obsessive-compulsive disorder, Binky Brown’s symptoms manifest as religious hallucinations and psycho-sexual fixations. Green revealed deep, shameful moments through a semi-autobiographical narrator.

His ability to visualise a private, interior illness had a profound effect on the future of comics as literature.

One artist inspired by Green was Art Spiegelman, who would go on to write the Pulitzer prize winning memoir Maus (1986).

Today, graphic medicine continues the underground tradition by exposing the silence around certain illnesses and sparking a new wave of publications both in print and online.

Brian Fies’ Mom’s Cancer (2004) chronicled his mother’s metastatic lung cancer in serial instalments: a poignant glimpse into the course of cancer treatment and its effect on both patients and their families.

Mom’s Cancer resonated with readers who saw themselves reflected in its images, anticipating the growing interest in stories about illness, disability and suffering – and a growing number of artists who wanted to share these stories.

In Marbles: Mania, Depression, and Michelangelo, and Me (2012), Ellen Forney explores her bipolar diagnosis by analysing the lives of other “tortured artists”. Julia Wertz’s The Infinite Wait and Other Stories (2012) looks at systemic lupus through a series of black-and-white graphic novellas.

Sarah Leavitt’s Tangles: A Story of Alzheimer’s, My Mother, and Me (2010) contemplates the uneasy role-reversal of caring for a parent with Alzheimer’s through a collection of notes and sketches spanning six years.

The experiences of medical professionals are also part of this genre.

Williams’ own graphic novel, The Bad Doctor (2014), depicts obstacles experienced by a general practitioner working in a small, rural town. In Taking Turns: Stories from HIV/AIDS Care Unit 371 (2017), M.K. Czerwiec combines her memories of working in a HIV/AIDS unit at the height of the AIDS crisis with oral histories from patients, families, staff and volunteers.

In my research, I have found graphic medicine points to intense cultural demand for stories of illness that are embodied, visual and subjective. New trends suggest these stories appear increasingly within the fluid and interconnected spaces of the internet, mapping new engagements with illness by collapsing the boundaries between authors and readers.

Far from the underground, these personal narratives traverse digital platforms and broadcast to vast communities.

They bring us even closer to the realities of living with illness.

The inclination to draw one’s self online has shifted from blogs like Hyperbole and Mom’s Cancer onto social media, where illness is embedded into how we represent our daily lives.

Alec MacDonald’s Instagram account, @alecwithpen emerged from a desire to regain control from chronic anxiety and depression. Like Brosh, MacDonald’s self-deprecating humour communicates an underlying struggle with mental health to over 270,000 followers.

In a cartoonish style, MacDonald uses metaphors to make his imaginings visible: childhood anxiety takes the shape of a giant, purple amorphous blob prone to swallowing him up; his black eye stands for parts of himself that shut down from mental illness and trauma.

View this post on Instagram

The immediacy and accessibility of the internet – with its relatively low threshold to publication – means stories of illness circulate as never before.

Throughout 2020 and into 2021, we have been routinely confronted with images of the pandemic: infographics of infection hot spots, photographs of mask wearing, medical illustrations, government advertisements and vaccine selfies. Throughout it all, COVID-19 comics from doctors, caregivers, patients and artists online gave voice to the humans in the story.

These works lay bare the vulnerabilities associated with experiencing, treating and witnessing illness, proving the power of drawing in capturing events that might not otherwise be possible to describe or understand.

Shannon Sandford, PhD Candidate, Flinders University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.