The US-based Commonwealth Fund conducts regular surveys of health care in 11 countries: Australia, Canada, France, Germany, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Sweden, Switzerland, the United Kingdom and the United States.

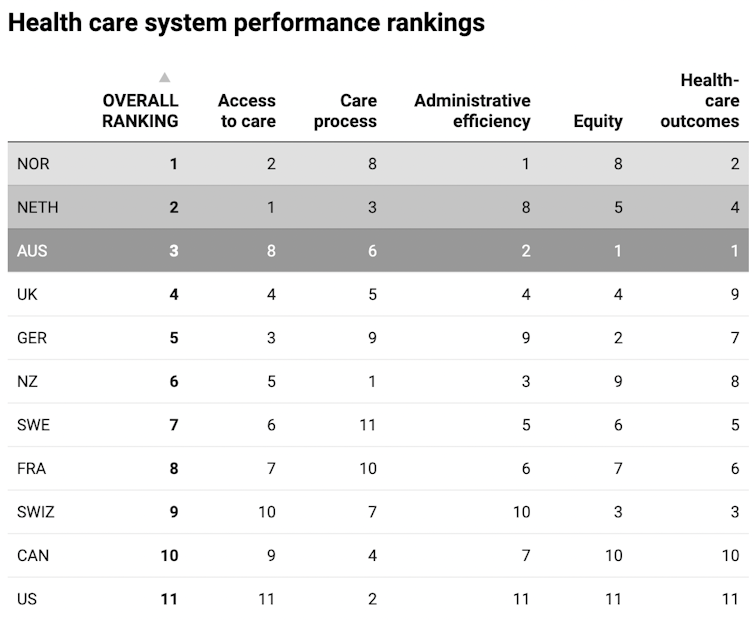

In its latest comparison, Australia ranks third overall, slipping from second in the previous comparison in 2017.

The US, not unexpectedly, ranks last overall, and last on four of the five component rankings.

Australia was awarded gold for two of the five component rankings: equity and health care outcomes.

The equity score is based on measures of disparity. For example, how different is access to care for people with above-average income compared to people with below-average income?

Australia’s Medicare scheme helps explain our good performance on this dimension.

Health care outcomes incorporates measures such as life expectancy and infant mortality rates.

Australia scored well on these and on outcomes of health care, such as the rate of women dying in childbirth, or of people dying in the month after being discharged from hospital after a heart attack.

Australia scored silver on administrative efficiency. Although primarily a measure of paperwork and its electronic equivalent, this also measures the ease with which medical practitioners can navigate the health system for their patients.

Australia’s good score again reflects well on Medicare as a single insurer. But it might also reflect Australia’s absence of a scheme requiring patients to get a second opinion from another doctor before surgery. Second opinions can be useful, so it might actually be disguising a shortcoming in the system.

Our overall score was dragged down by poor performance on the remaining two dimensions: access to care (where we were ranked 8th out of 11); and care processes (6th out of 11).

The first of these is not a surprise – stories about long waits for hospital care including elective procedures and outpatient appointments, and ambulance ramping, regularly feature in the media.

Poor affordability of dental care also contributed to Australia’s low score on access to care.

Australia performed somewhat better on access to primary care, which includes general practitioners.

More than 30 separate indicators were used to judge processes of care, for which New Zealand was awarded gold. Here, Australia was judged in the middle of the pack, doing moderately well on preventive care, and moderately well on “patient engagement/preferences”, such as nurses and doctors always treating patients with respect.

But it was dragged down by measures of safe care, such as failure to have alert systems to provide pathology results back to patients, and high hospital infection rates.

Australia’s processes of care score was also brought down by poor care coordination. For example, GPs aren’t necessarily notified when their patient presents to an emergency department. And specialists’ reports on patients aren’t sent to GPs within a week of the patient’s visit.

Problems with access to health care will not be easy to fix. The federal government has limited growth in its funding to the states for hospital care to 6.5% each year. This does not keep pace with growth in demand.

States can either find the additional money elsewhere to meet rising demand for health care (for example, by increasing state taxes such as payroll tax, or making cuts elsewhere). Or it can ration services, such as not providing enough operating theatre time (which results in longer waiting times for elective procedures). Or it can improve efficiency – and there is some scope for that in almost every state. States will typically do a mix of all three.

However, states alone can’t improve efficiency, because some measures fall within the federal government’s control. The federal government is responsible for primary care, for example, so it’s difficult for the states to design strategies to keep people out of hospital by making better use of primary care.

An easier option for states is to apply political pressure to get the federal government to lift the cap on funding and give the states more money. We can expect to see more of this in the lead up to the next federal election, which will be held before mid-May 2022.

Improving processes of care will also be difficult, but hopefully improved electronic patient records in hospitals will facilitate quicker communication between hospitals and GPs.

International comparisons help us identify opportunities to improve – but only if we avoid simply basking in a self-congratulatory glow from our high overall ranking.

The Commonwealth Fund survey is by no means perfect – there is some volatility in rankings of components from edition to edition – but it does allow us to drill down into the important attributes of health care, and to identify where others are doing better.

We should now set ourselves an agenda of what we want to learn and from whom.

Stephen Duckett, Director, Health Program, Grattan Institute

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.