In July 2019, the government introduced new aged care standards to “raise the bar” in an aged care system where some nursing home residents have experienced care that is neglectful, depersonalised, uncaring, unsafe and of poor quality.

We took a close look at breaches of aged care standards from 2019 to see what effect the new aged care standards are having, and where aged care providers are falling short.

In the interactive map below you can see aged care providers that were non-compliant in 2019.

Aged care standards are the minimum standard of care the government expects nursing homes to provide.

They are supposed to ensure people in aged care have access to quality care including competent staff who listen, best-practice clinical care and nutritious and tasty food.

Nursing homes that don’t meet standards are given a notice of non-compliance. If the provider doesn’t fix the problems that made it non-compliant, then it will be sanctioned.

If assessors decide there is an immediate and severe risk to residents, nursing homes can also be immediately sanctioned. The nursing home provider must then bring the care up to standard before they can take new residents.

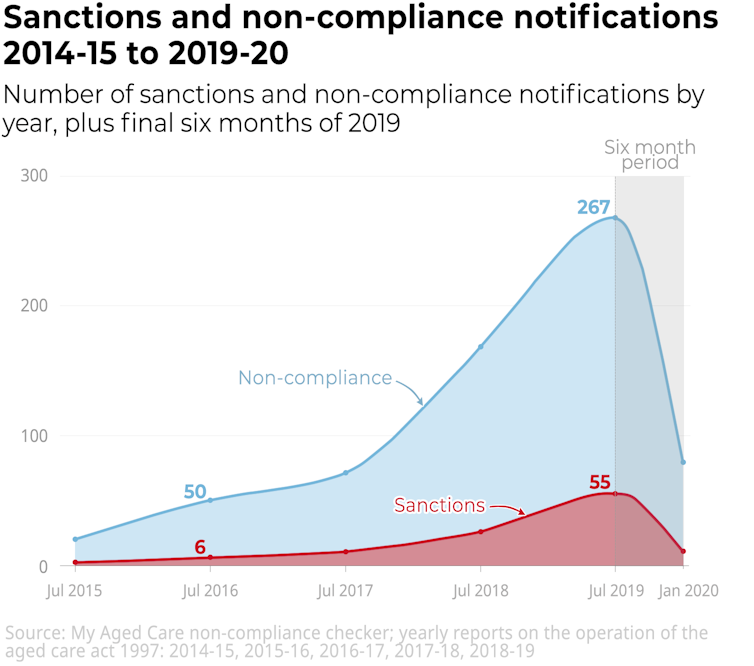

From 2014 until the new standards were introduced in July 2019, the number of non-compliance notices and sanctions increased steadily as can be seen in the chart below.

This was likely due to a combination of increasing scrutiny of the quality of residential care as a result of the unsafe care revealed at Oakden in 2017, and the establishment of the aged care royal commission in October 2018. A 2018 policy change meant providers were no longer warned about upcoming accreditation visits.

The new standards, introduced in July 2019, focus on “personal dignity and choice”.

They were designed to support the provision of care based on what residents want, rather than penalising providers when they let residents do something that could be considered “risky”, such as allowing someone with mild dementia to walk to the shops, or having a pet in the nursing home.

The number of non-compliance notices and sanctions in the first six months of the new standards decreased. This is likely because assessors visited fewer nursing homes in this period, and may still be learning how to interpret the new standards.

Aged care providers and industry bodies have criticised the new standards for being subjective and vague. They do not measure objective resident outcomes like depression or number of infections.

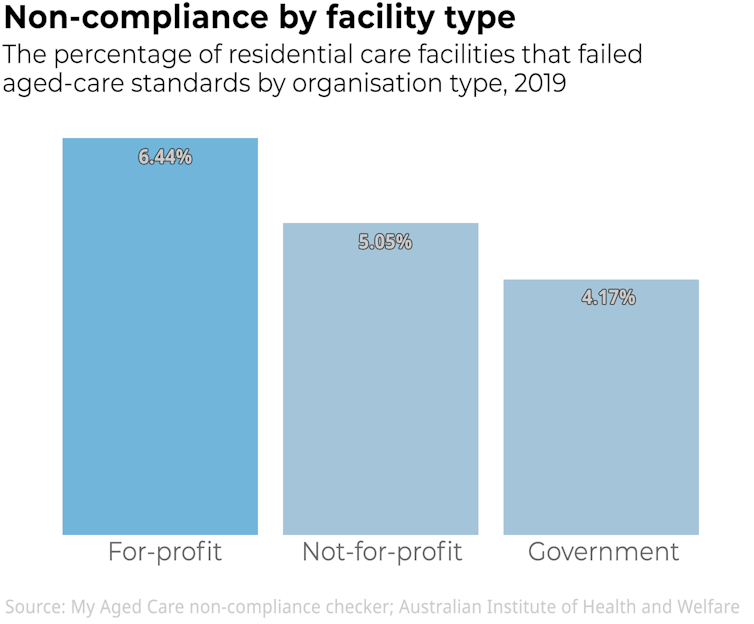

Some 6% of for-profit residential care facilities failed aged care standards in 2019, some of them multiple times. In comparison 5% of not-for-profit and 4% of government facilities failed standards.

The rate of non-compliance in for-profit facilities was 27% higher than not-for-profits, and 54% higher than government facilities.

This suggests for-profit providers in Australia are more likely to provide lower quality care. An international review has noted similar trends in other countries.

Profit margins are slim in aged care, and for-profit providers are under pressure to make profits by cutting costs. This could lead to a lower standard of care compared with not-for-profit or government providers.

The most common reasons for non-compliance in 2019 were in the area of personal and clinical care and the area of governance.

An example of a nursing home breaching the personal and clinical care standard could be if the home’s practices mean it isn’t giving medication correctly, isn’t managing wounds properly, or isn’t providing dignified help for residents using the toilet.

Homes might also breach the personal and clinical care standards if they don’t have sufficiently skilled staff such as registered nurses to care for residents with complex health needs.

A nursing home might be non-compliant in governance when it doesn’t have the right systems in place to monitor and improve its clinical care, for example in the areas of infection control or restraints. It might also be non-compliant if residents and families don’t have enough of a say in how the facility is run.

The new standards were supposed to place an increased focus on dignity and choice, supporting the identity of a person, and increasing their say in the care they receive. This means catering for residents who want to have showers in the evening, stay up late, or make their own lunch. Previously there was much less emphasis on these aspects of aged care.

It is somewhat promising that more breaches of non-compliance in the “dignity and choice” standard have been picked up since the new standards came in. But given we know care is often poor in this area and there is an increased focus on this standard, we could have expected a more significant change.

Based on the first six months of non-compliance and sanctions data for the new aged care standards, we cannot be confident the new standards are ensuring nursing homes provide higher quality care. We await more data.

Until then, aged care residents and their families should monitor the quality of care they receive, know their aged care rights, and complain if they think there is an issue.

If you or a family member are considering using an aged care provider, you can check whether the provider has breached standards via the My Aged Care non-compliance checker.

Lee-Fay Low, Associate Professor in Ageing and Health, University of Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.