This isn’t because of any special provisions the agreement contains, but because of a special provision that is missing.

As is common with trade and investment deals signed by the Australian government, the text was only made public after it was signed.

It will not have legal force until the parliament passes implementing legislation after a recommendation from the parliament’s Joint Standing Committee on Treaties, which will hold public hearings on Tuesday, Wednesday and Friday.

The Regulatory Impact Statement presented to the inquiry by the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade says the chapter on trade in services contains provisions that would “lock-in” existing regulation and require signatories to “not adversely modify existing regulation in particular services sectors”.

The provisions apply to all services other than those specifically exempted.

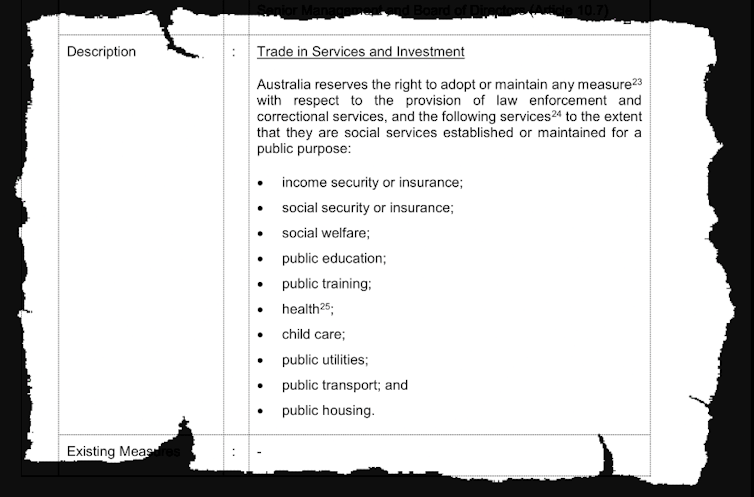

Australia included in an annex to the agreement a list of services that are specifically exempted, being “the specific sectors and sub sectors or activities for which Australia may maintain existing, or adopt new or more restrictive, measures”.

The list includes income security or insurance, social security or insurance, social welfare, public education, public training, health, childcare, public utilities, public transport and public housing. It does not include aged care.

The omission is puzzling, since childcare is included.

The footnotes add “for greater certainty” that the measures listed include

the protection of personal information relating to health and children, and add “for the avoidance of doubt”, that they include measures relating to the collection of blood and subsidies under Medicare and the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme.

There are no footnotes for the avoidance of doubt about aged care.

It might be that the government believes its ability to regulate for improved aged care standards is protected by the exemptions for “health services” and “welfare services”.

But United Nations classifications used in trade agreements code aged care differently from health care and social welfare services.

If the government really does intend to protect its ability to legislate for improved aged care standards, it would be well advised to add in a specific exemption for aged care, for the avoidance of doubt.

The Royal Commission into Aged Care Quality and Safety exposed multiple scandals caused by a lack of qualified staff and poor quality care, and recommended increases in staffing levels, increases in qualifications of staff and changes to licensing arrangements.

These are the types of tighter regulations the agreement could prevent, unless aged care is specifically exempted.

The Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership will bind Australia, New Zealand, China, Japan, South Korea, Brunei, Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, Myanmar, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, and Vietnam.

Companies considering investing in industries in those countries that aren’t specifically exempted (as aged care appears not to be in Australia) will be given an assurance that state and federal governments won’t tighten rules relating to

the total number of natural persons that may be employed in a particular service sector or that a service supplier may employ and who are necessary for, and directly related to, the supply of a specific service in the form of numerical quotas or the requirement of an economic needs test

As well, measures relating to qualification and licensing requirements must be “not more burdensome than necessary to ensure the quality of the service”.

The omission of a specific exemption for aged care might be an oversight.

When negotiations for the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership began in 2012, the aged care industry was dominated by local not-for-profits.

The sector is now dominated by for-profit providers, with a jointly-owned Singapore company, Opal, one of the largest.

Singapore is a party to the RCEP, giving it the right to initiate a state-to-state dispute before an international tribunal if it believes Australia has violated the agreement.

If the tribunal found in Singapore’s favour it could ban or tax Australian products. It is a possibility there might be time to avoid.

Patricia Ranald, Honorary research associate, University of Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.