When British TV doctor Michael Mosley died last year in Greece after walking in extreme heat, local police said “heat exhaustion” was a contributing factor.

Since than a coroner could not find a definitive cause of death but said this was most likely due to an un-identified medical reason or heat stroke.

Heat exhaustion and heat stroke are two illnesses that relate to heat.

So what’s the difference?

A spectrum of conditions

Heat-related illnesses range from mild to severe. They’re caused by exposure to excessive heat, whether from hot conditions, physical exertion, or both. The most common ones include:

- heat oedema: swelling of the hands, feet and ankles

- heat cramps: painful, involuntary muscle spasms usually after exercise

- heat syncope: fainting due to overheating

- heat exhaustion: when the body loses water due to excessive sweating, leading to a rise in core body temperature (but still under 40°C). Symptoms include lethargy, weakness and dizziness, but there’s no change to consciousness or mental clarity

- heat stroke: a medical emergency when the core body temperature is over 40°C. This can lead to serious problems related to the nervous system, such as confusion, seizures and unconsciousness including coma, leading to death.

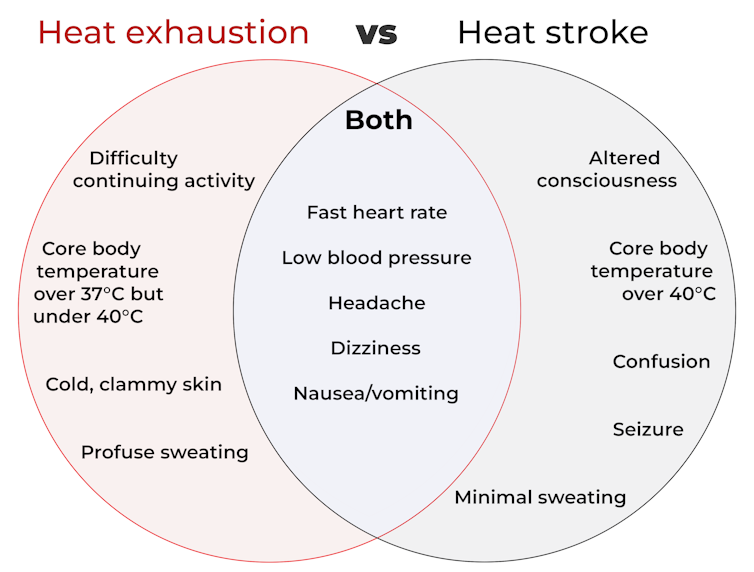

As you can see from the diagram below, some symptoms of heat stroke and heat exhaustion overlap. This makes it hard to recognise the difference, even for medical professionals.

How does this happen?

The human body is an incredibly efficient and adaptable machine, equipped with several in-built mechanisms to keep our core temperature at an optimal 37°C.

But in healthy people, regulation of body temperature begins to break down when it’s hotter than about 31°C with 100% humidity (think Darwin or Cairns) or about 38°C with 60% humidity (typical of other parts of Australia in summer).

This is because humid air makes it harder for sweat to evaporate and take heat with it. Without that cooling effect, the body starts to overheat.

Once the core temperature rises above 37°C, heat exhaustion can set in, which can cause intense thirst, weakness, nausea and dizziness.

If the body heat continues to build and the core body temperature rises above 40°C, a much more severe heat stroke could begin. At this point, it’s a life-threatening emergency requiring immediate medical attention.

At this temperature, our proteins start to denature (like an egg on a hotplate) and blood flow to the intestines stops. This makes the gut very leaky, allowing harmful substances such as endotoxins (toxic substances in some bacteria) and pathogens (disease causing microbes) to leak into the bloodstream.

The liver can’t detoxify these fast enough, leading to the whole body becoming inflamed, organs failing, and in the worst-case scenario, death.

Who’s most at risk?

People doing strenuous exercise, especially if they’re not in great shape, are among those at risk of heat exhaustion or heat stroke. Others at risk include those exposed to high temperatures and humidity, particularly when wearing heavy clothing or protective gear.

Outdoor workers such as farmers, firefighters and construction workers are at higher risk too. Certain health conditions, such as diabetes, heart disease, or lung conditions (such as COPD or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease), and people taking blood pressure medications, can also be more vulnerable.

Adults over 65, infants and young children are especially sensitive to heat as they are less able to physically cope with fluctuations in heat and humidity.

structuresxx/Shutterstock

How are these conditions managed?

The risk of serious illness or death from heat-related conditions is very low if treatment starts early.

For heat exhaustion, have the individual lie down in a cool, shady area, loosen or remove excess clothing, and cool them by fanning, moistening their skin, or immersing their hands and feet in cold water.

As people with heat exhaustion almost always are dehydrated and have low electrolytes (certain minerals in the blood), they will usually need to drink fluids.

However, emergency hospital care is essential for heat stroke. In hospital, health professionals will focus on stabilising the patient’s:

- airway (ensure no obstructions, for instance, vomit)

- breathing (look for signs of respiratory distress or oxygen deprivation)

- circulation (check pulse, blood pressure and signs of shock).

Meanwhile, they will use rapid-cooling techniques including immersing the whole body in cold water, or applying wet ice packs covering the whole body.

Take home points

Heat-related illnesses, such as heat stroke and heat exhaustion, are serious health conditions that can lead to severe illness, or even death.

With climate change, heat-related illness will become more common and more severe. So recognising the early signs and responding promptly are crucial to prevent serious complications.

Matthew Barton, Senior lecturer, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Griffith University and Michael Todorovic, Associate Professor of Medicine, Bond University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.