Whether it’s the market for hairdressers, for massage therapists or for general practitioners, usually the more of them there are in any town or suburb, the greater is the range and quality they offer and the lower the price.

It’s part of the thinking behind a range of government legislation designed to increase competition and consumer choice in residential aged care.

Yet in research just published by the Melbourne Institute using the de-identified records of 2,900 nursing homes provided to the aged care royal commission, we found no such effect.

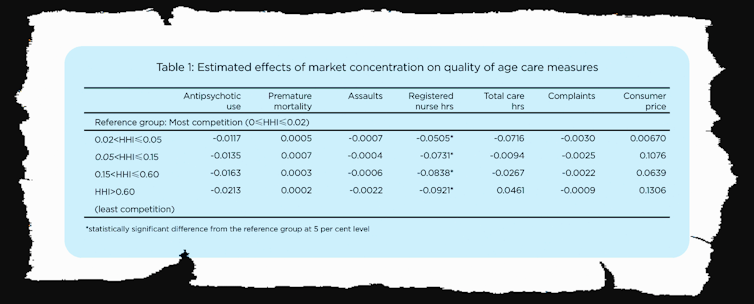

No matter how competition was measured, we found no statistically-significant differences in price or quality as indicated by a range of measures, including nursing hours worked per resident, assaults per resident, complaints per resident, the use of antipsychotic drugs and avoidable early deaths.

We measured the amount of competition for each nursing home in three ways: by the number of competitors within a 10-kilometre radius, the distance in kilometres to the nearest competitor, and a measure of market concentration known as the Herfindahl-Hirschman Index.

We found great variation in competition (much more in cities, much less in regions) along with slight decreases in competition in urban and remote areas (notwithstanding government measures designed to promote it) and minor increases in competition in regional Australia.

But we found no evidence linking competition to measures of quality of care, with the possible exception of registered nurse hours, although this linkage wasn’t present in all measures of competition.

Competition was weakly associated with price, if at all.

On the other hand, we found strong links between ownership and quality of care.

For most measures of quality, government-owned facilities provided much higher quality of care than for-profit providers and not-for-profit providers.

On prices, government-owned facilities charged by far the lowest price per resident per day – 23% lower than for-profits and 8% lower than not-for-profits.

In trying to think of the reasons why competition should not result in competition on prices or on the quality of service, a number of possibilities present themselves.

One reason is that demand for aged care places often arises suddenly due to significant changes in health conditions such as falls, dementia and loss of balance, meaning they have little choice but to use the first facility that becomes available.

Another is that consumers have little information about quality with which to make decisions. Unlike the United States and the United Kingdom, Australian authorities do not yet provide a five-star system of ratings that can be easily understood.

And prices are extremely hard to understand.

Demand often arises from consumers who experience sudden changes in their cognitive and physical conditions that make it difficult to search for information, and weigh options and exercise choice.

With users hamstrung, there are few market forces to discipline providers.

Measures that would help include publishing quality ratings (recommended by the royal commission), simplifying prices (not recommended, although the commission recommends an independent pricing authority) and providing consumer advocates to help people navigate through the system (recommended).

Given that most consumers transition from home care to residential care, it would help if advocacy services were integrated into home care services.

An alternative would be to abandon the pursuit of competition and set up a system of enforced standards, funded for different categories of care along the lines of the casemix system used in hospitals.

Although this was recommended in the commission’s final report, it would be harder to implement than it is in hospitals.

Aged care is about making life comfortable, whereas health care is about fixing problems, making consumer preferences much more important in aged care.

Harnessing the power of consumer preferences is a worthy goal, and there is a great deal we can do to move toward it, but there’s a long way to go.

Ou Yang, Research Fellow, The University of Melbourne; Anthony Scott, Professor, The University of Melbourne; Jongsay Yong, Associate Professor of Economics, The University of Melbourne, and Yuting Zhang, Professor of Health Economics, The University of Melbourne

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.