Anna Howe, Macquarie University

The Governor General was handed the report of the aged care royal commission on Friday. It will be made public in the coming week.

Overlaying its considerations has been Australia’s 909 deaths from COVID-19, more than two-thirds of them (685) people in aged care facilities.

It has to be recognised that COVID accounts for an extremely small share of deaths in Australia, and even deaths of senior citizens. 127,082 Australians aged 70 and over died in 2019. To date 851 in that age group have died of COVID.

Some good might come from these sad deaths if they prompted us to think about where we are likely to die.

Around half of all deaths of Australians aged 70 and over occur in nursing homes, but this neither means that nursing homes are particularly dangerous places nor that a large proportion of Australians aged over 70 are in them at any one time.

At any one time only about 9% of Australians in their seventies and beyond are in nursing homes, and those days are their final ones.

Some will not stay for long – one in five admitted to permanent care will stay less than 6 months, and half for around 18 months – but others will stay for three years or more.

The unpredictability of the length of stay makes it hard for us to be sure we can fund it ourselves.

Many would prefer to die somewhere else; at home, perhaps in our sleep, but few will have such luck. Even fewer will die in an accident, either on the roads or somewhere else. Quite a few will die in an acute care hospital after a serious illness.

Read more:

At the heart of the broken model for funding aged care is broken trust. Here’s how to fix it

Although we generally want to be cared for in our home for as long as possible, there are limits to what is possible, and acceptable. Not all of us have our own home, or one that is suitable for care. Large numbers of us have no living family members, or no family members able to provide the needed care.

Adult children of those in their late 80s or 90s are often in their 60s and have their own problems with health and disability. Some live far away, and others are estranged.

Even high levels of in-home community care can leave very frail individuals lonely and fearful, and family and other carers exhausted. So admission to a nursing home becomes inevitable.

Death and taxes were once the only certainties, but paying tax is far less certain these days, especially among retirees after the 2006-07 Howard-Costello budget abolished the tax on most super fund earnings and payouts in retirement.

The Grattan Institute has demonstrated that many young workers are paying more tax than retirees on much higher (tax-free) incomes. These well-off retirees are as much “taxpayer subsidised” as “self funded”.

The Royal Commission has already flagged the need for large increases in aged care funding.

Read more:

We’ve had 20 aged care reviews in 20 years – will the royal commission be any different?

About 80% of the operating cost of residential aged care is funded directly by the Commonwealth. The remaining 20% comes from “user contributions”, much of which comes from Commonwealth age pension payments.

Means-tested fees not funded by the pension account for less than 5% of costs.

Which raises the question of where the increased funding would come from.

One of the Royal Commission’s consultation papers canvassed private insurance and social insurance.

History suggests that private insurance is not a viable option: the private health insurance coverage of nursing home benefits that was in place from 1977 to 1981 ended with government bailouts at an eventual cost to the Commonwealth budget.

Read more:

Modelling finds investing in childcare and aged care almost pays for itself

Internationally, the take-up of private long-term care insurance is low and unstable, even in the United States.

Social insurance has better prospects, and a Medicare-type levy offers a tempting solution. But in the current climate with wage growth down to record lows, even a 1% levy might struggle to gain acceptance.

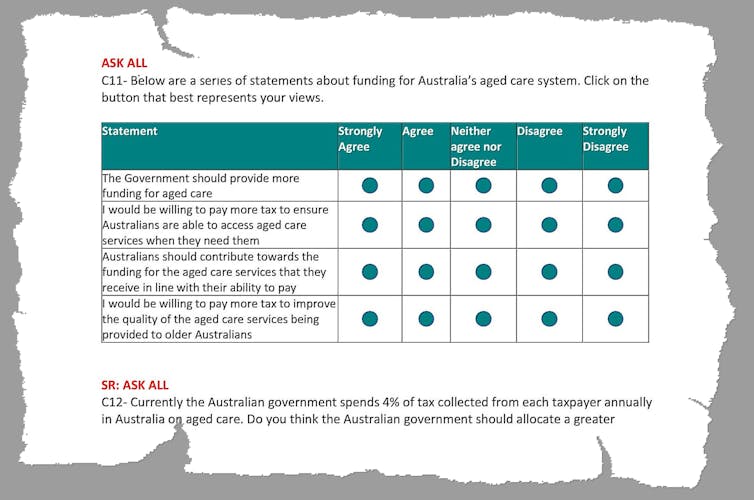

Research conducted for the Commission about public views on aged care funding found that close to 90% thought “the government should provide higher funding”.

But many of those surveyed did not seem to connect “the government” with taxes.

Almost 40% of those who currently pay income tax said they would not be willing to pay any more tax to provide for aged care, with the rest divided evenly between those willing to pay 0.5% more tax, 1% more tax, or even more.

The Association of Superannuation Funds reports that 25% of women and 13% of men reach retirement with no super.

In contrast, it finds the 10% able to make large extra contributions (most of them men and nearly all of them high earners) have average balances of $500,000 and in many cases balances of well over $1 million).

Read more:

We need super, but we’re taxing it the wrong way round

They are the ones who get the bulk of the concessions on super fund earnings

Clawing back $5 billion per year from those concessions would cover about a quarter of the Commonwealth’s residential aged care bill of around $20 billion.

It could be done by applying a 5% “aged care levy” to the earnings of the top quarter of super fund balances held by those aged 50 to 70.

As well as redressing some of the inequities in the super, an aged care levy would link super to the risk of needing aged care, a more common risk than many appreciate.

Applying the levy only to people near to or early post retirement would be fairer than applying it to all age groups – all of whose taxes go towards funding the super concessions.

Despite the hopes of some who are trying to come up with ways of funding better aged care, very few of the very old who are admitted to residential care have the capacity to pay more towards its cost, either now or in the foreseeable future.

Even among those who have lots of super, few will have enough to last to the time they are admitted to residential care in their late 80s or 90s.

And wealth stored in the form of housing faces the same problem.

Like wealth stored as super, it is unevenly distributed. One in four Australians aged 65 and over are renters, and have few if any assets to draw on.

Among homeowners, the value of wealth stored in housing varies widely and can be eroded with advancing age.

Most of those entering aged care are very old women. It will be a great day when they have high incomes and are able to pay their way, but it is a long way off.

Meantime, will knowing that we have a one in two chance of ending our lives in an aged care home make us more committed to improving the system after COVID-19 and the Royal Commission?

Probably not. For many of us the day of reckoning is far away, we have other things to think about, we think things will change, and we hope we will be in the other half of the population who die elsewhere.

Anna Howe, Honorary Professor, Department of Sociology, Macquarie University, Macquarie University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.